This is an exclusive extract from The Immortals by Arrigo Sacchi, which tells the story of Milan‘s 1988-89 European Cup-winning season.

Here, Sacchi explains why winger Angelo Colombo was so important to his Milan team, despite being a less-glamorous name than some of his teammates – who included Franco Baresi, Ruud Gullit and Marco Van Basten – but also why, ultimately, Colombo was sold in 1990.

Football Italia has four copies of The Immortals to give away, as well as an exclusive interview with Luigi Garlando, the journalist who collaborated with Sacchi on the book.

Colombo’s butler

European Cup

First round, first leg Vitosha Sofia 0 Milan 2

The day before we made our European Cup debut against Vitosha, Silvio Berlusconi came to our team hotel in Sofia. It was the afternoon, and I was asleep. That in itself was strange because I usually never took a nap after lunch, plus I had several reasons to be losing, rather than gaining sleep, at least in the afternoon. For example, there was the emotion of taking my first steps in the competition that I’d dreamed about since I was a kid, and the absence of three of the team’s pillars, one per department: Baresi, Ancelotti, Gullit.

However, the summer friendlies against prestigious clubs had given me a great sense of calm – they’d been the confirmation that the team had assimilated the principles of our game really well. And when you have a game, you can sleep well, even when you’re missing players.

Perhaps the three Vitosha spies who had watched us score three times against Real Madrid were not quite so serene. “And that was without Van Basten,” they kept reminding one another.

After being woken up, I came downstairs to say hello to Berlusconi, who greeted me with a smile. “Just like the Prince of Conde*, sleeping before the battle!” And just like the French at Rocroi, we won, in the exact manner that Gullit had predicted when chatting with the media the day before the game.

* In Alessandro Manzoni’s Promessi Sposi (The Betrothed), a seminal work in Italian fiction, he recalls how the Prince of Conde always slept well before battle, because he was so sure of his planning and strategy

“My teammates will score in the first half, then I’ll come on to finish the job.” Virdis did indeed score, in the 18th minute. In the 70th minute, he was replaced by Ruud, who took only five minutes to find the back of the net.

We dominated from start to finish, much more than the scoreline suggests. The Bulgarians were completely taken aback by our pressing. Costacurta – a 22-year-old kid – proved an able replacement for Franco Baresi, while Rijkaard, the best player on the pitch, gave a stupendous performance.

Vasil Metodiev, the Vitosha coach, was impressed by Colombo’s display, to the extent that in the post-match press conference he said he was his man of the match. In addition to being one of the key figures in the pressing that ultimately won us the game, Angelo had delivered the crosses for both goals.

One day, the 1982 World Cup winner Ciccio Graziani, asked me: “What have you done with that lad? When he played with me at Udinese, if I went to the near post, he crossed to the far post. If I went to the far post, he crossed to the near post. If I went to both of them, he’d hit the ball straight out.”

Galbiati was an important figure. He didn’t just have an influence on the pitch – he would talk to the players and smooth over the most spiky of situations; a true diplomat, experienced and full of good sense. That Milan would not have existed had we not become a team off the field as well; had we not shared the same idea. From president Berlusconi to the people working in the kit store, everyone played their part to perfection. The doctors, Giovanni Battista Monti and Rodolfo Tavana; the psychologist, whom I needed more than the players; Paolo Taveggia, the team manager; poor old Guido Susini, the head of communications. Plus, naturally, Adriano Galliani, one of the best directors in the history of world football. Passionate, brilliant, never intrusive, even though he knew the game inside out.

I remember Tokyo and the scenes after Evani’s lastminute goal in the Intercontinental Cup final against Medellin. I saw a man in an overcoat come onto the field and run to the centre circle. I thought it was a pitch invader – nope, it was Galliani.

Angelo Colombo was a key piece on my Milan chessboard. He never tired of running and he did it very intelligently: he knew where and how to run, even without the ball. He gave crucial help to the defence, and was just as precious in our attack. Thanks to the way he covered and the way he moved in space, his more technically gifted teammates could express the best of themselves. For this reason, in the dressing room you’d often hear a chant of: “Fly, Colombo, Fly!”

When Real Madrid were celebrating their centenary, they gave me the task of putting together and coaching a Rest of the World select. As soon as I ran into Rafael Gordillo, the left-back who always came up against him on the flank, I told him: “I’ve brought Colombo.” The colour instantly drained from his cheeks. “No, no, I’ve had quite enough of Colombo!” What battles when those two great runners went head-to-head.

Angelo Colombo was not an absolute talent. He wasn’t the sort of star player who you can rely upon to boost primetime ratings. Indeed, at the time when Borghi’s arrival was being discussed, Berlusconi threw that back in my face: “I haven’t spent 100 billion [Lire] to watch Colombo play!”

My reply? “As long as I’m manager, whoever deserves to play, will play.”

In time, though, the president probably understood that it was the team who needed to shine on prime-time TV, not individual players, and that Colombo was just as big a contributor to Milan’s beauty as anyone else. Indeed, when I told him in 1990 that we needed to sell Angelo, Berlusconi tried to change my mind.

I’d called Colombo to my office and spoken clearly to him. “Angelo, this isn’t good enough. With this level of effort and these returns, you can’t stay at Milan.”

With huge honesty, Angelo replied: “Boss, I’ve gone beyond my wildest dreams. I’m drained. You’re right – I’m no longer managing to give what I did before. I don’t have the same motivation.”

I told Berlusconi, who wanted us to take our time. “Let’s wait and give him a few months. Maybe he’ll get back to his old ways. He’s always been important for us.”

A couple of months later, I went to see the president again. “I’m sorry, but nothing’s changed. We need to sell Colombo.”

Once more, Berlusconi sought to mediate. I stopped him and said: “Define Angelo Colombo.” The president thought for a moment, then reached for a cycling term: “He’s a domestique.”

“Quite,” I replied. “Well, I phoned Angelo’s house one day and it was the butler who responded, saying, ‘the master is not home’. Have you ever heard of a domestique with a butler?”

Berlusconi agreed to the sale, and it earned him some decent money from Bari. For the sake of honesty, I told Gaetano Salvemini – the Bari coach at the time – how it had gone with Angelo, but they still wanted to give him a two-year contract worth 750m Lire per season.

Our debut had gone well. I’d won my first match in the European Cup, but judging by the calmly scientific comments in my log-book, I didn’t get too excited.

Good result. A good match defensively but only just good enough in attack. To be improved: the collective shaking off of markers, and our cover movements.

Berlusconi seemed much more excited than I was, opting for a metaphor inspired by one of his favourite passions: “We’ve started pulling on the skirt of Europe. Let’s hope we’re looking her in the eyes before long.”

At that point, the second leg at the San Siro appeared to be a formality, but a series of unfortunate coincidences changed the picture quite incredibly.

First of all, four of my men were called up by the motherland for the Seoul Olympics: Colombo, Tassotti, Evani and Virdis – half the starting team.

Then, on September 20 during a training session, Gullit collapsed to the ground, screaming, with nobody near him. He’d twisted his ankle and would be in plaster for a month. Ancelotti was still out, Costacurta and Maldini had problems too, and Van Basten had gone back to Holland for treatment. To call it an emergency would have been an understatement.

Indeed, on September 21, in the neutral surrounds of Bergamo with a team full of youngsters, we couldn’t manage more than a draw with Osvaldo Bagnoli’s Verona. Claudio Caniggia put them ahead and then Baresi equalised.

On September 29 we lost 1-0 to Torino, whose goal was a Giorgio Bresciani penalty. We were out of the Coppa Italia while Verona went through. I told you that place brought me bad luck.

I sounded the alarm. I asked the club to approach UEFA and request the second leg of the Vitosha match be moved at least a couple of days from October 6 to 8, so that I could get a few players back. I also used the press to flash a warning sign to the Milanello dressing rooms: “We scored two goals in Sofia, but we can easily lose three at home,” I said.

I deliberately left out one detail. Among the returning players, even though he had still to reach 100 per cent, was a centre-forward called Marco van Basten.

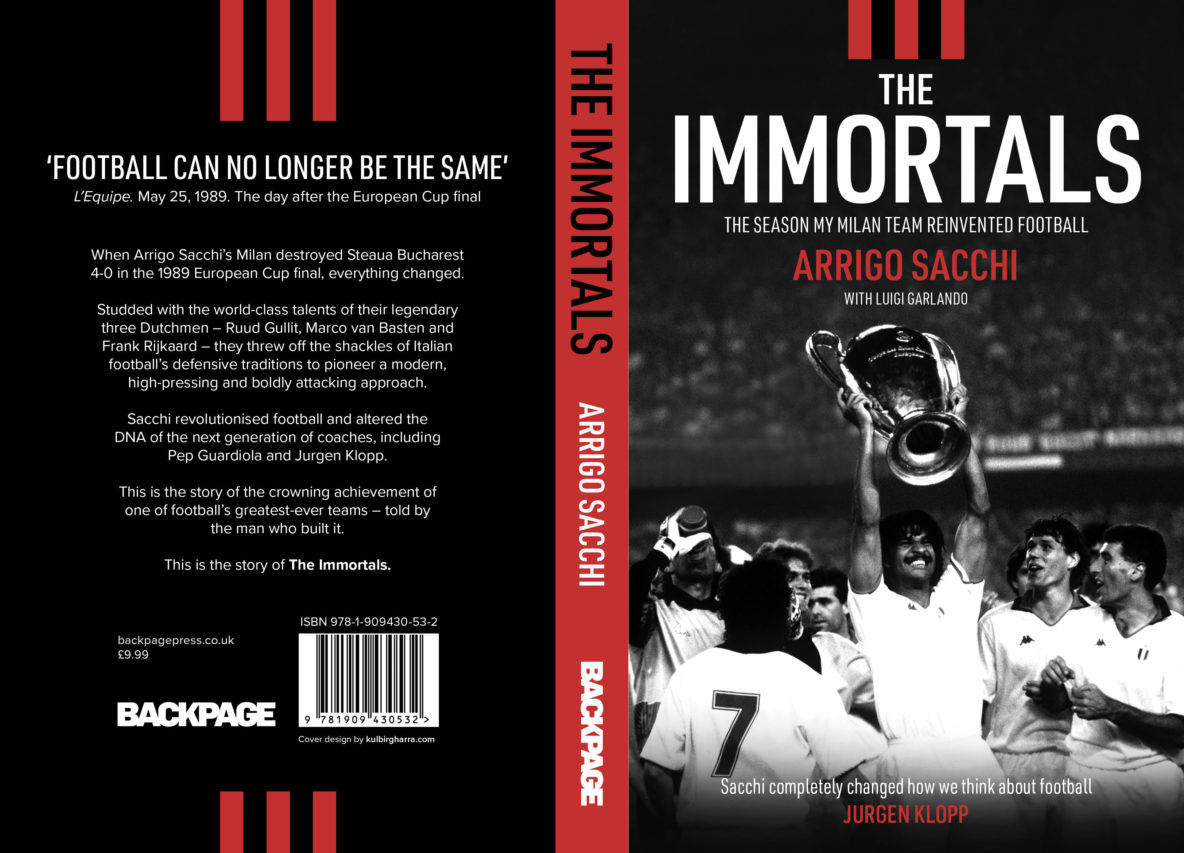

The Immortals by Arrigo Sacchi is out now in paperback and ebook, published by BackPage.

Unfortunately Sacchi didn’t win the European Cup three times in a row, he almost did.

Unfortunately his golden touch only applies to AC Milan 88-90, not to the other teams that he coach after AC Milan, he ruined with the Azzurri and ruined the careers of many Italian players by not calling them to La Nazionale because of his personal problems with them.

But he is still a pioneer at his era, a maestro and a dirigent that orchestrated an attractive game that makes football very interesting. An attacking football that is relentless and pressing the opponent with very high.

Utter disgrace what he did in 94 wc final, we all loved baggio but he was injured from bulgaria game and yet this guy did not play signori, in fact not only was baggio injured but so did gentile and they both missed, with a super sub signore we would have won that thing and Donnaruma agent is right about saying that he should have won that WC